Women are better at recognising illness in faces than men: Study

The ability to recognize illness in others is an essential skill that can help prevent the spread of diseases and provide timely support to those in need. While it is often assumed that this skill is innate and equally distributed among individuals, a recent study has found that women are better at recognizing illness in faces than men. This fascinating discovery has significant implications for our understanding of human behavior, social interactions, and the role of evolution in shaping our abilities.

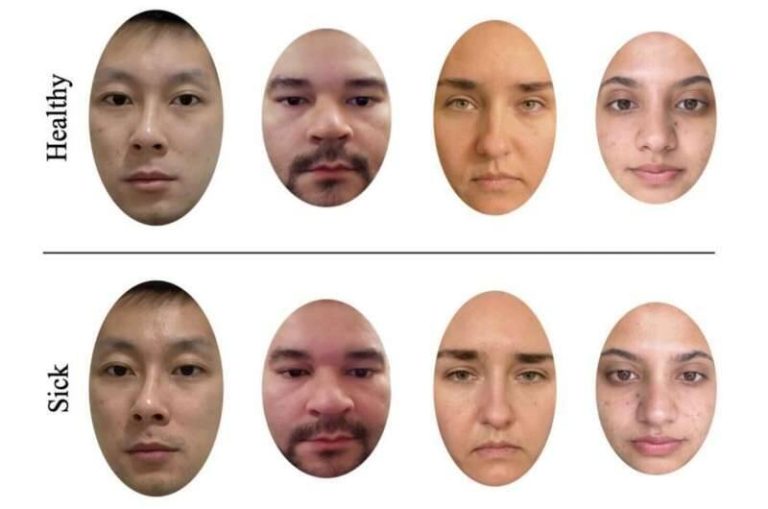

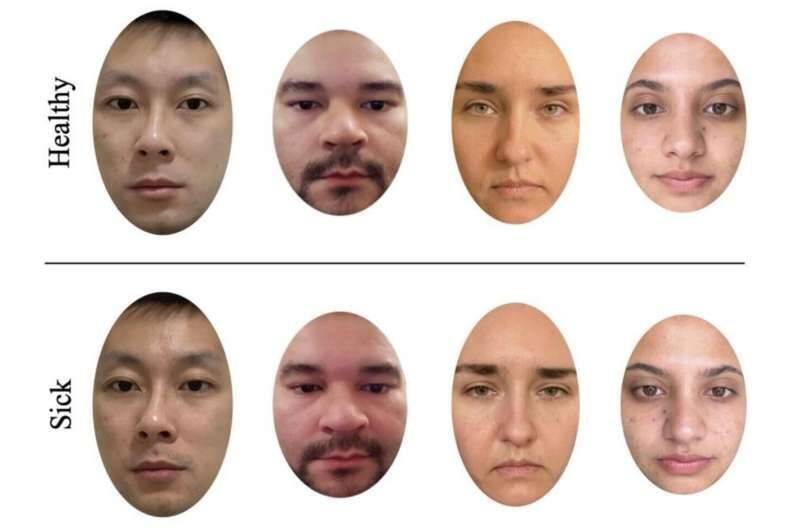

The study, which recruited 140 males and 140 females, asked participants to rate 24 photos of individuals in times of sickness and health. The photos were carefully selected to depict subtle signs of illness, such as pale skin, dark circles under the eyes, and changes in facial expression. The participants were then asked to rate the health of each individual in the photo, with higher ratings indicating better health.

The results of the study showed that women were significantly better at recognizing illness in faces than men. On average, women correctly identified 75% of the sick individuals, while men correctly identified only 55%. This difference was statistically significant, suggesting that women have a more developed ability to detect illness in others.

The study proposed two hypotheses to explain why women might be better at recognizing illness in faces. The first hypothesis suggests that women have evolved to detect illness better as they have historically taken on more caregiving roles, such as caring for infants and children. This would have required them to be more attentive to subtle changes in health and behavior, allowing them to provide timely support and prevent the spread of diseases.

The second hypothesis proposes that women are more empathetic and socially sensitive than men, which enables them to pick up on subtle cues in facial expressions and body language. This increased emotional intelligence would allow women to better recognize the emotional and physical states of others, including signs of illness.

Both hypotheses are supported by evolutionary theory, which suggests that women have faced stronger selection pressures to develop caregiving skills and social sensitivity. Throughout history, women have played a crucial role in caring for children, the elderly, and the sick, which has required them to be highly attuned to the needs and emotions of others. This has likely led to the development of specialized cognitive and emotional abilities, including the ability to recognize illness in faces.

The findings of this study have significant implications for our understanding of human behavior and social interactions. They suggest that women may be more effective at providing care and support to others, particularly in situations where subtle signs of illness need to be detected. This could have important implications for fields such as healthcare, education, and social work, where women are often underrepresented.

Furthermore, the study highlights the importance of considering the role of evolution in shaping human behavior and cognition. By recognizing the different selection pressures that men and women have faced throughout history, we can gain a deeper understanding of the cognitive and emotional abilities that have developed in each sex.

In conclusion, the study provides strong evidence that women are better at recognizing illness in faces than men. The proposed hypotheses, which suggest that women have evolved to detect illness better due to their caregiving roles and increased emotional intelligence, are supported by evolutionary theory and have significant implications for our understanding of human behavior and social interactions. As we continue to explore the complexities of human cognition and behavior, it is essential to consider the role of evolution and the different selection pressures that have shaped our abilities.

For more information on this study, please visit: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1090513825001527

News Source: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1090513825001527