Women are better at recognising illness in faces than men: Study

When it comes to detecting illness, women may have an edge over men. A recent study has found that women are better at recognising illness in the faces of sick people compared to men. This fascinating discovery has sparked interesting discussions about the possible reasons behind this phenomenon. In this blog post, we will delve into the details of the study, its findings, and the possible explanations for why women might be better at detecting illness in faces.

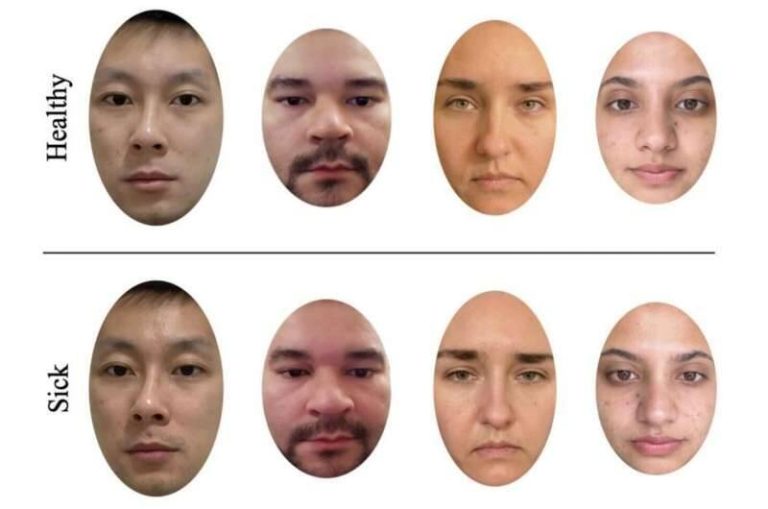

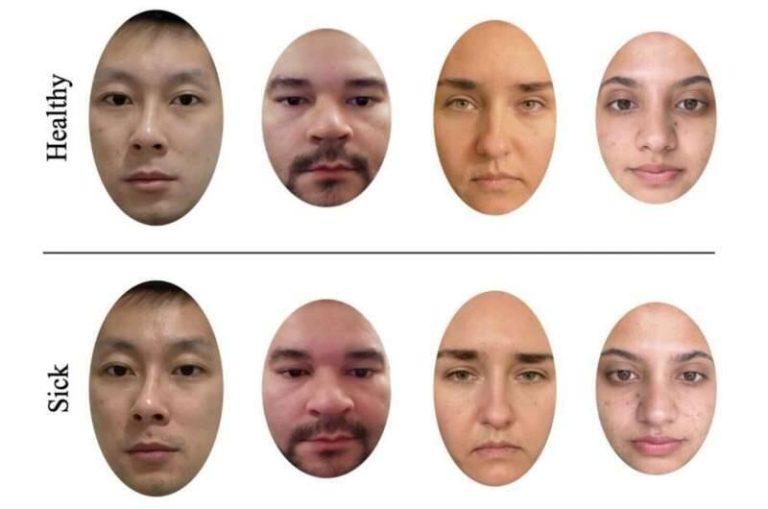

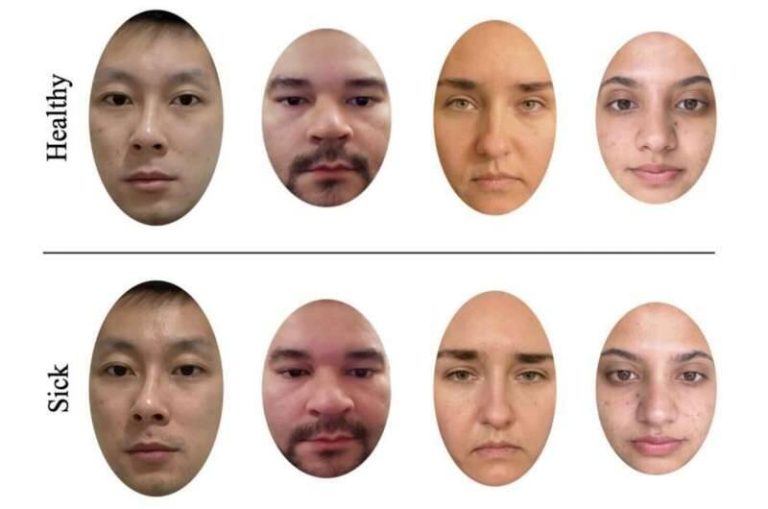

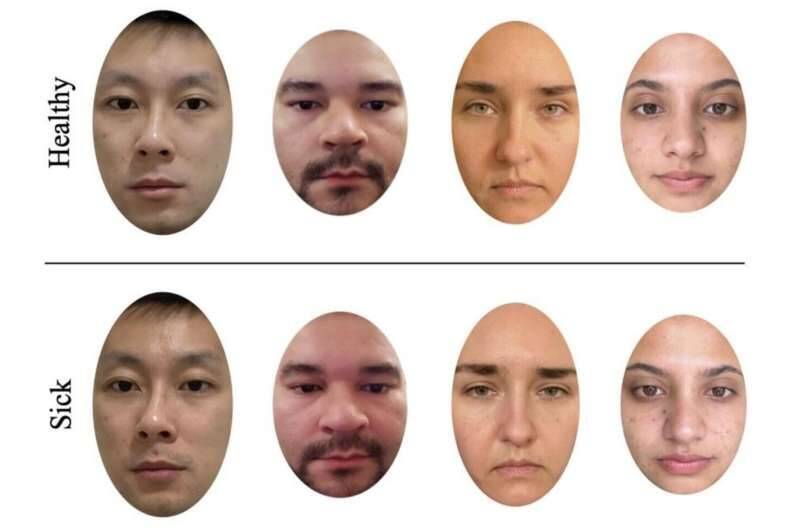

The study, which recruited 140 males and 140 females, asked participants to rate 24 photos of individuals in times of sickness and health. The photos were carefully selected to ensure that the subjects’ facial expressions, clothing, and background were consistent, making it easier to focus on the subtle cues that might indicate illness. The participants were then asked to rate the health of each individual in the photo, with higher ratings indicating better health.

The results of the study showed that women were significantly better at recognising illness in the faces of sick people compared to men. This difference was consistent across all 24 photos, suggesting that women’s superior ability to detect illness was not limited to specific types of illnesses or facial expressions. The study’s findings have important implications for our understanding of how humans perceive and respond to illness, and may even have practical applications in fields such as medicine and healthcare.

But why might women be better at detecting illness in faces? The study proposed two hypotheses to explain this phenomenon. The first hypothesis suggests that women may have evolved to detect illness better as they took care of infants and young children. Throughout history, women have played a primary caregiving role, responsible for nursing and caring for their children when they are sick. This experience may have honed their ability to detect subtle cues of illness, such as changes in facial expression, skin tone, and body language.

The second hypothesis proposes that women may be more attuned to social and emotional cues, which could help them detect illness more effectively. Women are often socialized to be more empathetic and nurturing, which may make them more sensitive to the emotional and social signals that people send when they are sick. For example, a woman may be more likely to notice that a person is avoiding eye contact or seems withdrawn, which could be indicative of illness.

Both of these hypotheses are supported by existing research on sex differences in social perception and caregiving. Studies have shown that women are generally more accurate at reading facial expressions and detecting emotional cues, which could help them detect illness more effectively. Additionally, women’s experience with caregiving may have given them an edge when it comes to recognizing the subtle signs of illness.

The study’s findings have important implications for our understanding of how humans perceive and respond to illness. If women are indeed better at detecting illness in faces, this could have practical applications in fields such as medicine and healthcare. For example, women may be more effective at diagnosing and treating illnesses, particularly those that are difficult to detect through traditional medical tests.

Furthermore, the study’s findings could also have implications for our understanding of sex differences in social perception and caregiving. If women are more attuned to social and emotional cues, this could help explain why they are more likely to take on caregiving roles and why they may be more effective at detecting illness.

In conclusion, the study’s findings suggest that women are better at recognising illness in faces than men. The proposed hypotheses, which suggest that women may have evolved to detect illness better as they took care of infants and young children, or that they may be more attuned to social and emotional cues, are supported by existing research on sex differences in social perception and caregiving. The study’s findings have important implications for our understanding of how humans perceive and respond to illness, and may even have practical applications in fields such as medicine and healthcare.

For more information on this study, please visit: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1090513825001527