Women are better at recognising illness in faces than men: Study

The ability to recognize illness in others is a crucial aspect of human social interaction. It allows us to provide care and support to those who need it, while also protecting ourselves from potential health risks. A recent study has shed new light on this topic, revealing that women are better at recognizing illness in the faces of sick people compared to men. This fascinating finding has significant implications for our understanding of human behavior, social interaction, and the role of evolution in shaping our abilities.

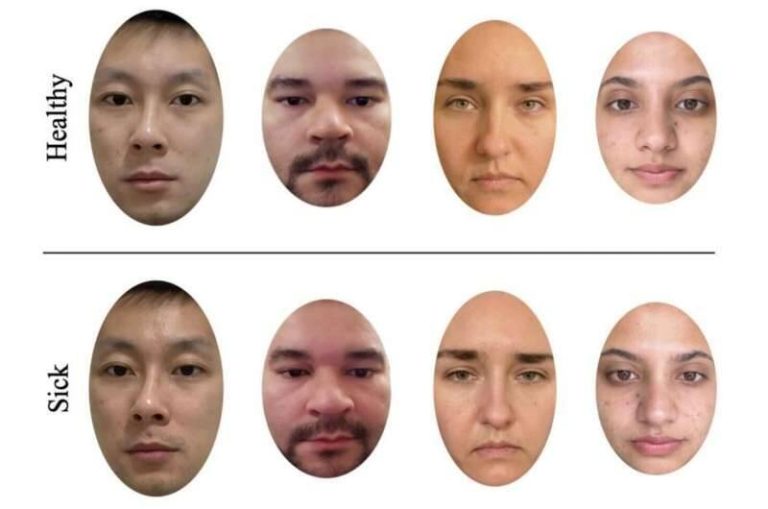

The study, which recruited 140 males and 140 females, asked participants to rate 24 photos of individuals in times of sickness and health. The photos were carefully selected to ensure that the only visible difference between the healthy and sick images was the presence of illness. The participants were then asked to rate the photos based on how sick or healthy they perceived the individual to be. The results showed that women were significantly better at recognizing illness in the faces of sick people, with a higher accuracy rate compared to men.

But why might women be better at recognizing illness in faces? The study proposes two hypotheses to explain this phenomenon. The first hypothesis suggests that women may have evolved to detect illness better due to their historical role in caring for infants and children. Throughout human history, women have taken on a primary caregiving role, responsible for nurturing and protecting their young from harm. This has led to the development of specialized skills and abilities, including the ability to recognize early signs of illness in their children. By being able to detect illness more effectively, women can provide timely care and support, increasing the chances of their child’s survival and well-being.

The second hypothesis proposes that women may be more attentive to social cues, including facial expressions and body language. This increased attention to social cues may allow women to pick up on subtle changes in a person’s appearance, such as pale skin, sunken eyes, or a weak smile, which can be indicative of illness. This hypothesis is supported by previous research, which has shown that women tend to be more empathetic and socially aware than men, with a greater ability to read and interpret social signals.

The study’s findings have significant implications for our understanding of human behavior and social interaction. They suggest that women may play a critical role in detecting and responding to illness in their social networks, including family, friends, and community members. This is particularly important in the context of infectious diseases, where early detection and response can be critical in preventing the spread of illness.

The study also highlights the importance of considering evolutionary factors in shaping human behavior and abilities. The fact that women may have evolved to detect illness better due to their historical role in caring for infants and children is a powerful example of how evolutionary pressures can shape our abilities and behaviors. This finding challenges the traditional view that human behavior is solely the result of cultural or environmental factors, and instead suggests that our evolutionary history plays a significant role in shaping who we are and how we interact with the world around us.

In conclusion, the study’s findings that women are better at recognizing illness in faces than men are both fascinating and significant. They highlight the importance of considering evolutionary factors in shaping human behavior and abilities, and suggest that women may play a critical role in detecting and responding to illness in their social networks. As we continue to navigate the complexities of human social interaction, it is essential that we consider the role of evolution in shaping our abilities and behaviors, and recognize the unique strengths and abilities that women bring to the table.

For more information on this study, please visit: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1090513825001527

News Source: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1090513825001527