Cells ‘Vomit’ Waste to Heal Injury Faster: Study

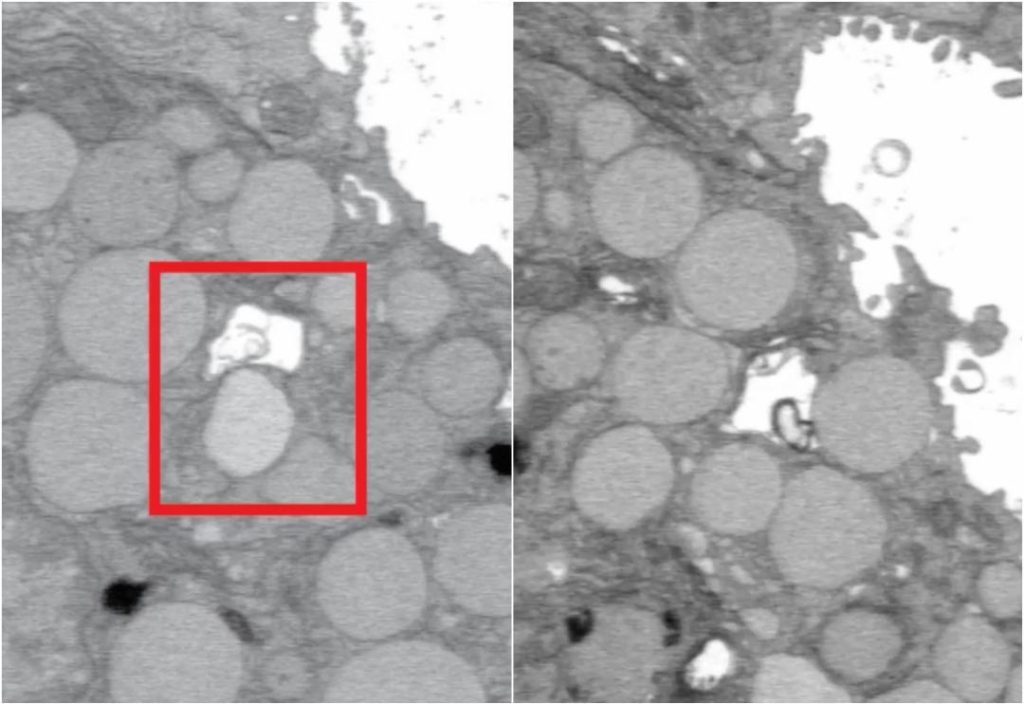

A groundbreaking study has shed light on a previously unknown process in which cells undergo a form of “vomiting” to rid themselves of damaged components and rapidly heal injuries. The research, published in the journal Cell Reports, reveals that this process, called cathartocytosis, enables cells to adapt to stress and injury by rapidly becoming smaller and more efficient at healing.

The study, conducted in mice, has significant implications for our understanding of cell biology and its potential applications in the treatment of diseases and injuries. The researchers have also warned that persistent cathartocytosis can be a sign of chronic inflammation and recurring cell damage, which is a known risk factor for cancer.

Cells are the building blocks of all living organisms, and they are incredibly complex structures that play a vital role in maintaining our overall health. However, when cells are injured or stressed, they can become damaged and dysfunctional, leading to a range of diseases and disorders. The development of new treatments for these conditions often relies on a deeper understanding of the processes that occur within cells during injury and stress.

In this study, researchers from the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) and the University of California, San Diego (UCSD) used advanced imaging techniques and biochemical analysis to investigate the response of cells to injury. They found that when cells are stressed or injured, they undergo a process called cathartocytosis, in which they release damaged components into the surrounding tissue.

This process is similar to the way that our stomachs “vomit” food particles and toxins when we are ill. However, in cells, cathartocytosis is a highly regulated process that involves the release of damaged components, such as proteins and organelles, into the surrounding tissue.

The researchers found that cathartocytosis is a rapid and efficient process that enables cells to rapidly adapt to stress and injury. During this process, cells release damaged components and simultaneously upregulate their ability to repair and regenerate damaged tissue.

The study also found that cathartocytosis is a highly coordinated process that involves the activation of specific signaling pathways and the expression of specific genes. The researchers identified a number of key players in this process, including a protein called PINK1, which is involved in the regulation of cathartocytosis.

The findings of this study have significant implications for our understanding of cell biology and its potential applications in the treatment of diseases and injuries. The researchers suggest that the development of new treatments for diseases may rely on the ability to modulate cathartocytosis and promote the rapid healing of injured tissues.

However, the study also warns that persistent cathartocytosis can be a sign of chronic inflammation and recurring cell damage, which is a known risk factor for cancer. The researchers suggest that further studies are needed to fully understand the mechanisms underlying cathartocytosis and its potential impact on human health.

In conclusion, this study has shed new light on the complex and fascinating world of cell biology. The discovery of cathartocytosis, a process in which cells “vomit” waste to heal injury faster, has significant implications for our understanding of the mechanisms underlying cell injury and stress. While further research is needed to fully understand the implications of this study, it is clear that the findings have the potential to lead to the development of new treatments for a range of diseases and disorders.

Source:

https://www.cell.com/cell-reports/fulltext/S2211-1247(25)00841-1