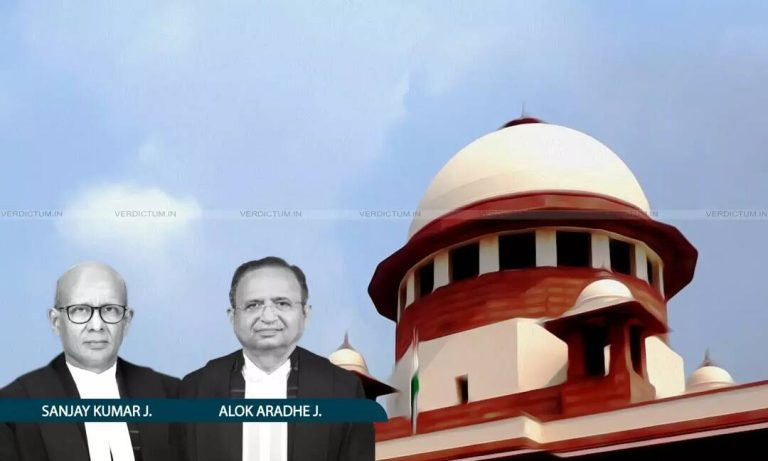

Substitution of Sole Arbitator Warranted Once Mandate Ends: SC

The Supreme Court of India has recently made a significant ruling in the realm of arbitration law, specifically addressing the circumstances under which the substitution of a sole arbitrator is warranted. In its judgment, the Court has held that once the mandate of a sole arbitrator ceases to exist, their substitution is indeed warranted. This decision has far-reaching implications for the conduct of arbitration proceedings in India and underscores the importance of adhering to the procedural timelines and requirements as outlined in the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996.

At the heart of this matter is the understanding of the arbitrator’s mandate and the consequences of its expiry. The Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996, provides a framework for arbitration in India, including provisions related to the appointment, tenure, and responsibilities of arbitrators. The Act also specifies the circumstances under which an arbitrator’s mandate can be terminated or when their substitution becomes necessary.

The Supreme Court’s ruling clarifies that upon the expiry of the initial or extended period granted for the completion of the arbitration proceedings, the arbitrator’s mandate automatically terminates. This termination is subject to a court order that may be passed in a proceeding under Section 29A(4) of the Arbitration and Conciliation Act. Section 29A(4) pertains to the extension of the arbitrator’s mandate beyond the prescribed period, which can be done through a court order, thereby allowing the arbitration to continue beyond the initial time frame.

The significance of this ruling lies in its emphasis on the time-bound nature of arbitration proceedings. The Arbitration and Conciliation Act aims to ensure that disputes are resolved efficiently and within a reasonable timeframe. The expiry of the arbitrator’s mandate, therefore, marks a critical juncture where the continuation of the proceedings requires either the arbitrator’s substitution or a court-sanctioned extension.

The Court’s decision is also noteworthy for its implications on the principle of party autonomy in arbitration. While parties have the freedom to agree on the procedure for arbitration, including the appointment and tenure of arbitrators, this autonomy is not absolute. The Arbitration and Conciliation Act imposes certain limits and requirements to ensure that arbitration proceedings are conducted in a fair, efficient, and timely manner. The substitution of a sole arbitrator upon the cessation of their mandate reflects a balance between party autonomy and the need for procedural integrity.

In practical terms, this ruling means that parties to an arbitration agreement must be vigilant about the timelines associated with the arbitration process. They must ensure that the arbitrator’s mandate is either extended in accordance with the Act or that a substitution process is initiated promptly upon the expiry of the mandate. Failure to do so could lead to unnecessary delays or even the termination of the arbitration proceedings, which could ultimately undermine the dispute resolution process.

The Supreme Court’s judgment is a reminder of the dynamic nature of arbitration law in India, which is continually evolving through judicial pronouncements. As the legal landscape continues to shift, it is essential for legal practitioners, arbitrators, and parties involved in arbitration to stay abreast of the latest developments and interpretations of the Arbitration and Conciliation Act.

In conclusion, the Supreme Court’s ruling that the substitution of a sole arbitrator is warranted once their mandate ceases to exist underscores the importance of adhering to procedural timelines and requirements in arbitration proceedings. This decision reinforces the principles of efficiency, fairness, and party autonomy that underpin the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996. As arbitration continues to grow as a preferred method of dispute resolution in India, the clarity provided by this judgment will be invaluable in ensuring that arbitration proceedings are conducted in a manner that is both legally sound and practically effective.