Women are better at recognising illness in faces than men: Study

The age-old adage “a picture is worth a thousand words” has taken on a new meaning in the context of a recent study that suggests women are better at recognising illness in the faces of sick people compared to men. The study, which was conducted by a team of researchers, aimed to investigate the differences in how men and women perceive and detect illness in facial expressions. The findings of the study have significant implications for our understanding of the role of evolution, socialisation, and cognitive abilities in shaping our ability to detect illness.

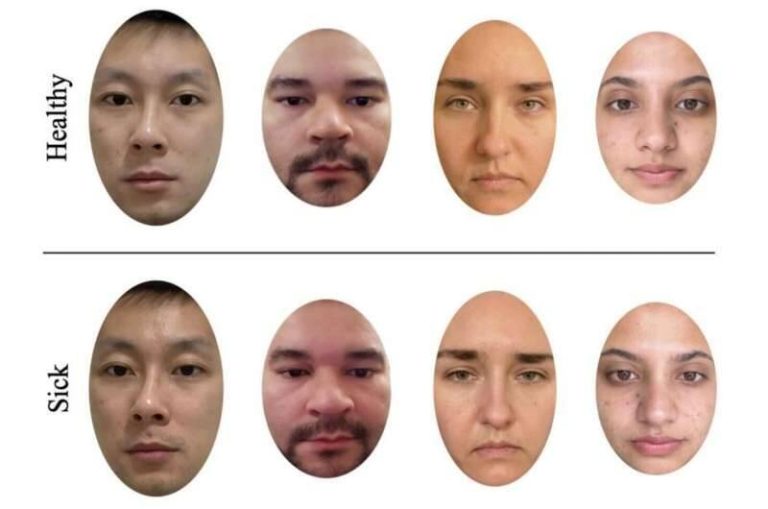

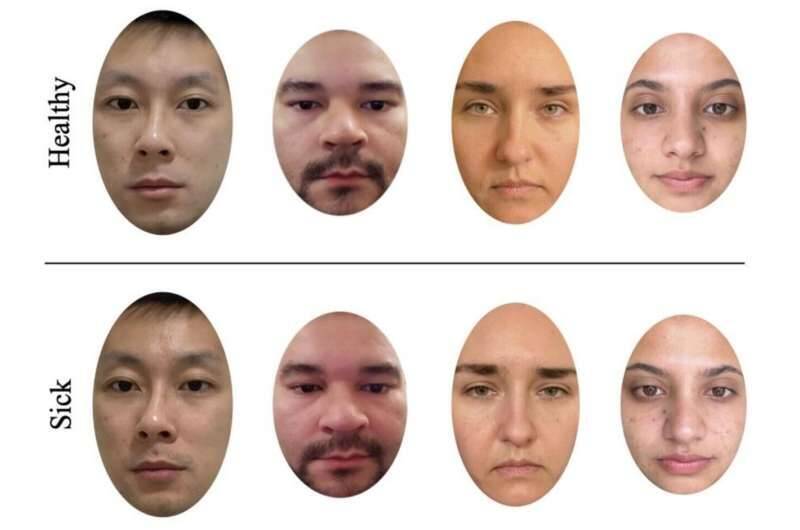

The study recruited a total of 280 participants, consisting of 140 males and 140 females, who were asked to rate 24 photos of individuals in times of sickness and health. The photos were carefully selected to depict a range of illnesses, including respiratory infections, skin conditions, and other visible signs of illness. The participants were then asked to rate the photos based on how sick or healthy they perceived the individual in the photo to be. The results of the study showed that women were significantly better at recognising illness in the faces of sick people compared to men.

The study stated two hypotheses for this finding, suggesting that women might have evolved to detect illness better as they took care of infants and young children, who are more vulnerable to illness and disease. This hypothesis is based on the idea that throughout history, women have played a primary role in childcare and healthcare, and as such, have developed a keen sense of observation and detection when it comes to illness. The second hypothesis suggests that women may be more empathetic and attentive to the emotional and social cues of others, which could also contribute to their ability to detect illness more accurately.

The findings of the study are consistent with previous research that has shown that women tend to be more empathetic and emotionally intelligent than men. Women are also more likely to engage in nurturing and caregiving activities, which require a high degree of emotional sensitivity and social awareness. These traits, the study suggests, may have evolved in women as a result of their historical role in childcare and healthcare, and may now be applied to a wider range of social and emotional contexts, including the detection of illness.

The study’s findings also have significant implications for our understanding of the role of evolution in shaping human behaviour and cognition. The fact that women are better at recognising illness in faces suggests that there may be an evolutionary advantage to being able to detect illness, particularly in the context of childcare and healthcare. This advantage may have driven the development of specialised cognitive and emotional abilities in women, which are now reflected in their superior ability to detect illness.

The study’s results also raise interesting questions about the role of socialisation and cultural norms in shaping our ability to detect illness. For example, are women more likely to be socialised to pay attention to the emotional and social cues of others, which could contribute to their ability to detect illness? Or are there cultural or environmental factors that influence our ability to detect illness, and if so, how do these factors vary across different populations and contexts?

In conclusion, the study’s findings suggest that women are indeed better at recognising illness in faces than men, and that this ability may have evolved as a result of their historical role in childcare and healthcare. The study’s results have significant implications for our understanding of the role of evolution, socialisation, and cognitive abilities in shaping our ability to detect illness, and highlight the importance of considering the social and emotional context in which illness is detected and responded to.

The study’s findings also have practical applications in a range of fields, including healthcare, education, and social work. For example, healthcare professionals may be able to use the study’s findings to develop more effective training programs for detecting illness, which take into account the differences in how men and women perceive and respond to illness. Similarly, educators and social workers may be able to use the study’s findings to develop more effective interventions and support programs for individuals who are sick or vulnerable to illness.

Overall, the study’s findings are a fascinating addition to our understanding of human behaviour and cognition, and highlight the importance of considering the complex interplay between evolution, socialisation, and culture in shaping our abilities and behaviors.

News Source: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1090513825001527