Women are better at recognising illness in faces than men: Study

A recent study has shed light on the differences in how men and women perceive and recognize illness in others. The study, which involved a total of 280 participants, found that women are significantly better at identifying sickness in people’s faces compared to men. This fascinating discovery has sparked interesting discussions about the possible reasons behind this difference, with some hypotheses suggesting that women’s evolutionary roles may have contributed to their enhanced ability to detect illness.

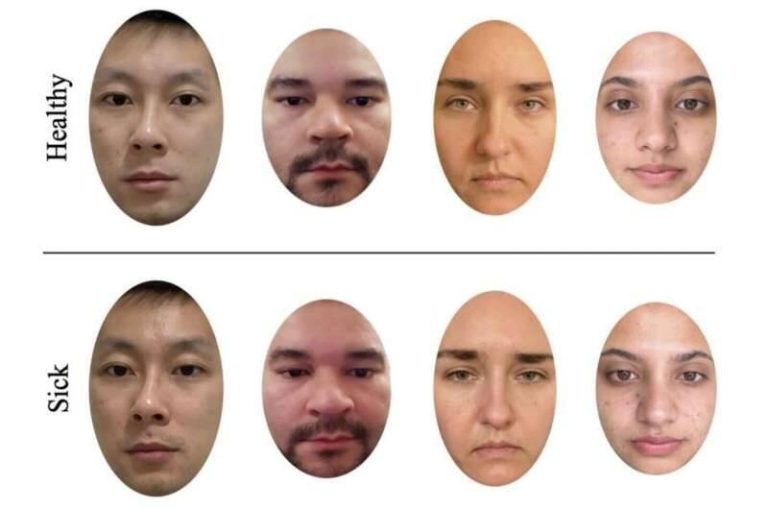

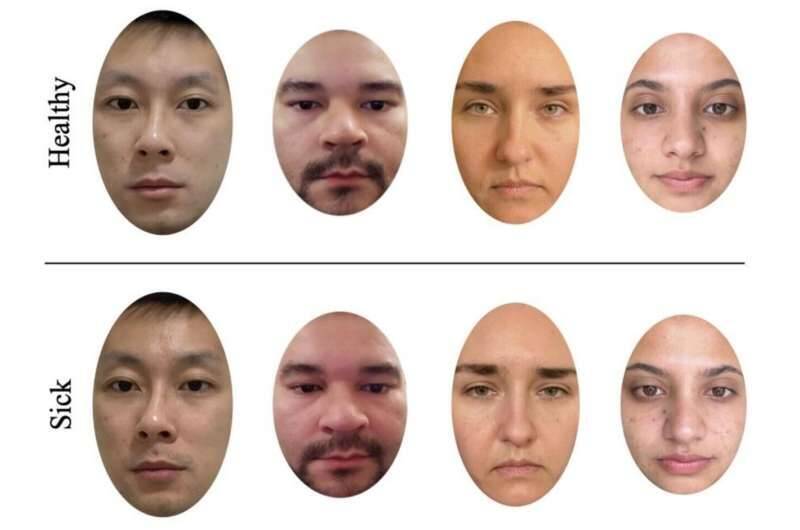

The study recruited 140 males and 140 females to participate in a photo-rating exercise. The participants were shown 24 photos of individuals, taken at times when they were both sick and healthy. The photos were carefully selected to ensure that the only difference between the healthy and sick versions was the presence of illness. The participants were then asked to rate the photos based on how sick or healthy they perceived the individual to be.

The results of the study were striking, with women consistently outperforming men in recognizing illness in the photos. On average, women were able to correctly identify sickness in 83% of the photos, while men were only able to do so in 74% of the cases. This significant difference suggests that women may have an innate ability to detect illness, which could have important implications for various fields, including healthcare and social interactions.

The study’s authors proposed two hypotheses to explain why women might be better at recognizing illness in faces. The first hypothesis is based on the idea that women have evolved to be more attentive to the needs of others, particularly in the context of childcare. Throughout history, women have often taken on the primary role of caring for infants and young children, who are more susceptible to illness and require constant monitoring. As a result, women may have developed a heightened sense of awareness for subtle changes in facial expressions and other nonverbal cues that can indicate illness.

The second hypothesis suggests that women may be more empathetic and socially attuned than men, which could also contribute to their ability to recognize illness. Women tend to be more skilled at reading social cues and understanding the emotional states of others, which could help them pick up on subtle signs of illness that might be missed by men. This hypothesis is supported by previous research, which has shown that women tend to perform better on tasks that require empathy and social understanding.

The study’s findings have important implications for our understanding of how men and women perceive and interact with each other. In healthcare settings, for example, women’s ability to recognize illness could be a valuable asset in diagnosing and treating diseases. Additionally, the study’s results could inform the development of more effective healthcare interventions, such as training programs that focus on improving men’s ability to recognize illness.

The study also raises interesting questions about the role of evolution in shaping human behavior and cognition. If women’s ability to recognize illness is indeed an evolutionary adaptation, it suggests that our brains are capable of reorganizing and adapting to changing environmental pressures over time. This idea challenges the traditional view of the brain as a fixed entity and highlights the importance of considering the complex interplay between biology, culture, and environment in shaping human behavior.

In conclusion, the study’s findings provide compelling evidence that women are better at recognizing illness in faces than men. While the exact reasons for this difference are still unclear, the study’s hypotheses offer intriguing possibilities for further research and exploration. As we continue to learn more about the complex factors that influence human perception and behavior, we may uncover new insights into the intricate relationships between biology, culture, and cognition.

For more information on this study, please visit: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1090513825001527